When a child sits for hours on homework with go math 6 grade, especially in elementary school, parents rightly consider this situation abnormal and begin to help – they take over presentations and reports, get involved in solving problems and examples. Just to make sure the child does not get a bad grade. But there is also the opposite view of school stress and failure – that they are useful for growing up.

Homework is different: exercises and preparation for the test, useful and meaningless, exciting and completely frustrating. But no matter what kind of homework is involved, and no matter how you personally feel about its purpose or meaningfulness, homework is in any case for the child, not for you. Your responsibility is to be supportive. Encourage, direct the child’s attention while he is small, and when he grows up – clearly articulate the requirements for it, and no more prying.

Don’t do your homework together with your child – for his future

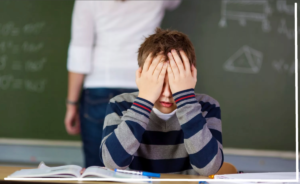

Yes, I know, I know: it’s easier said than done. It’s not so hard to step aside and give your child autonomy when the assignment in first grade go math is simple enough – like solving standard examples – or when a deadline for a big project looms safely somewhere in the distant future. But when the whining and complaining in the vein of “I don’t want to do my homework” and “It’s very difficult!” escalates into yelling, it is tempting to take matters into your own hands or simply give the right answer, so that this torture can end and all family members can return to normal life.

You can’t give in to this temptation. These moments of stress, when the child’s frustration level is off the charts, are a valuable opportunity to develop diligence, perseverance and hard work. A child is just learning not to give up and fight to the end, when he has hard, when he was already confident that nothing will work, when he suffers from the consequences of his own procrastination, or inability to plan. This is where you should not just take a step back, but leave altogether.

It may not seem like much trouble to interfere, but this kind of damage accumulates cumulatively. Every time you intercept an assignment and save your child the trouble of solving a difficult math problem or writing a science paper, you undermine his confidence and his autonomy. Handling the assignment yourself is a powerful incentive, a reward far more valuable than grades and test scores. Focus on the long term.

Soon enough, you’ll forget the assignment your child spent half the night working on; he may not remember how this poster or this task seemed out of his depth. He will forget the specifics, but what will remain are the long-term good consequences of the hours he spent figuring out a math problem on his own, or conducting a science experiment until he got his own results.

Yes, the child may have to be disappointed in his efforts, or even in his abilities, if he appears before his teacher and classmates in the morning with the wrong answer, but he needs those lessons. Your duty – not to save your child from disappointment and embarrassment, but to sympathize, support and help him to find the strength and skills to do the next task.

Let the child make the same discovery that this schoolgirl made, fighting in the middle of the night with both math and her inner voice.

One night, as I was struggling with the last particularly difficult math problem, I suddenly thought, “What if I don’t fight the proof? What if I just gave up?” I knew I would get the job done eventually, but it would take a long time, and I just didn’t want to sit around. I pondered this for quite a while and eventually put down my textbooks and went to bed – but I woke up a few hours later: I was woken up by the urge to finish the case. At about one o’clock in the morning I jumped up and produced the proof I needed. Although I was terribly tired, I felt great, and I knew I had done a great job. I hadn’t been so happy with myself and my schoolwork in a long time.

How much do they ask for a house in the USA

This schoolgirl clearly benefited from a one-on-one struggle with a math task, although parents, teachers and journalists fiercely argue about whether there is at least some pedagogical value in homework. The State Pedagogical Association (National Educational Association, NEA) in the “Study of the situation with homework” (Research Spotlight on Homework) came to the conclusion: “Overloading with homework is the exception rather than the rule.” The association further confirmed that ” the majority of American schoolchildren, regardless of class, devote less than an hour a day to homework, and this situation has persisted for almost the entire last 50 years.”

As for the “homework crisis” – indeed, tasks have increased now, but only for two categories of students: for junior high school students (who were traditionally not loaded at all) and for specialized (gymnasium, lyceum, etc.) classes aimed at preparing for university. On the contrary, the volume of assignments in the middle and high grades of most schools, especially those that do not strive for great achievements, has remained stable since the 1950s, and in schools in disadvantaged areas, whose graduates do not expect anything, there are almost no homework.

The recommendations of the National Parent-Teacher Association (National PTA) serve as the standard with which most schools compare the volume of homework, and these recommendations stem from the most authoritative studies on the effectiveness of the time that should be spent on homework: 10-20 minutes a day for first-graders and beyond, plus 10 minutes in each next class.

If the child does his homework until the night

If a child complains that he spends too much time on homework or does not manage to do everything at all, I advise parents to first quickly check all the items from the list below, and then discuss this situation with the teacher.

Check the child’s vision and hearing. Problems with them can lead to a violation of understanding and a decrease in study results.

Make sure that the child gets enough sleep. According to the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), babies need 11-13 hours of sleep, from 5 to 10 years old they need 10-11 hours, and adolescents need from 8.5 to 9.25 hours of sleep nightly. Reduced sleep affects concentration, memory, attention, abilities, executive functions and behavior.

Take a closer look at how the task itself is performed. When I hear from parents that a child spends hours sitting over a notebook, I try to follow this student imperceptibly during recess or performing an independent task in the classroom. Some guys seem to be working, but looking closely, I am convinced that they spend a lot of time, jump from task to task, start and quit, meaninglessly scribble something. And this is without a smartphone, computer and other distractions at hand.

If you think that there are too many tasks, try doing this exercise at home: sit next to the child while he does the task, and note the moments when he is moving forward, and when he is engaged in all sorts of nonsense or stalling. This way you will get an objective idea of how much time is spent on real work in the aggregate.

If the “clean time” still seems too long to you, then determine which subjects are” to blame ” for this most of all, and talk to the appropriate teachers about excessive workload.

If the teachers answer that your child is in the minority, and the children spend no more than a reasonable amount of time on homework, try the Time Recipe.

We are conducting an experiment

The recipe for Time was invented by math teacher Alison Gorman, a high school teacher. She noticed that some students spend a long time tinkering with tasks at home, but in the classroom, when the same examples are assigned as independent work, there are no distractions and limited time is allocated, these guys manage to pass the work on time, and sometimes earlier than required.

The recipe for Time looks like this: find out which subject takes the most time from the child, and calculate how much time it takes every day. For example, let’s assume that this is mathematics. If a student spends an hour and a half on it, cut the time in half, set a timer for 45 minutes and warn that as soon as this time expires, math will be finished and you will have to take other subjects. Set the timer so that the child can see it and can watch how time passes.

Please warn that you should not spend half an hour on the first example — then you will not be able to cope with the entire task in 45 minutes, you need to calculate the time correctly. And you know what? In nine cases out of ten, your student will meet the deadline.

Talk to the teacher in advance, warn about the planned experiment: with a high probability, the teacher will agree to give the child some relaxation for a while. At least he will be warned about why one or two examples may remain unfinished, and this information will also be useful to him. He will be able to figure out exactly what type of tasks causes difficulties for the child, and for his part will contribute to the fact that the Recipe of Time will benefit the student.